SeaMe is a museum installation that allows children to design fish and bring them to life in a virtual underwater world. The fish are created with normal arts and crafts supplies and cut out with scissors. A web-cam, combined with software image analysis, captures an image of the fish and inserts it into the SeaMe environment. The virtual fish become dynamic, autonomous creatures that interact with the world around them. The application is designed for children aged 7-11.

The Vision

At the outset of our project, we had a few key insights about what makes a good learning exhibit:

- Physicality: Kids are more likely to engage with objects that can clearly be physically manipulated

- Experimentation: Exhibits that keep children engaged for the longest time allow children to experiment with little to no cost of failure. Children seem truly excited about failures that are wild, dangerous, or downright wacky.

- Personalization: Children feel pride upon completion of their own artifacts. Regardless of whether the work is successful or not, children are incredibly excited to have a creation to call their own.

We decided to combine the physicality of traditional crafts projects – designing, coloring, cutting – with a digital world in which children could experiment. The virtual aquarium environment allows us to simulate living creatures with different, quirky behaviors that draw the interest of children. By sticking with a physical creation process, we keep children creatively engaged in a world they are familiar with, while allowing them a larger degree of freedom than software can provide. At the end of the process, a child is left with his or her own paper fish, while its virtual twin swims around in the SeaMe tank.

Learning Goals

Our original goal was to simulate an underwater environment in which fish compete to survive, similar to real world ecosystems. After talking to the head of education at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, we initially focused on creating fish behaviors relating to 1. What a fish ate and how it did so 2. How a fish defended itself from predators and 3. How a fish grouped with or remained isolated from its peers.

As our project developed, we found that children tended to focus on three other attributes our contact at the Monterey Bay Aquarium had mentioned, namely:

- Kids aged 7-11 love things that are weird, gross, or unusual

- They relate new information to what they are already familiar with and

- They are used to rich, visual media

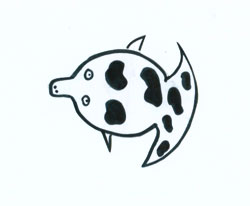

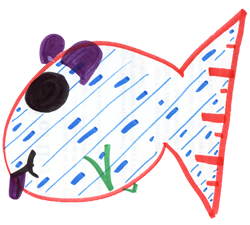

Kids we observed loved creating wild, outlandish fish with vibrant colors. We wound up with fish like “Idiocy Fish,” “Abe Lincoln on a Surfboard,” “Artistic Fish,” and “World Fish” swimming around in the SeaMe world. Kids did not want to create realistic fish that were well-adapted for survival, they wanted to create fish that related to their everyday world or fish that were truly wacky. What they truly enjoyed was the process of experimentation involved in the creation of a virtual fish. Due to time constraints, we focused primarily on improving the quality of the creation process – getting the fish inside the SeaMe world – and provided a small set of wacky behaviors based on the color of the fish. Our final learning goals were:

- Experimentation with the creation system: We want to give kids a robust system that maps objects in the physical world to ones in our virtual world. Kids would invariably wind up experimenting with physical objects besides paper fish – hands, faces, toy soccer balls – and we think encouraging such creative experimentation is valuable.

- Exploration of the behavior space: We have a handful of wacky behaviors that map to a handful of dominant fish colors. We never actually tell kids what leads to what behavior. We want to encourage them to come up with hypotheses and test them out by creating new fish.

Prototyping

SeaMe presented two big design challenges: How do we get a fish on paper into the fish tank? and How do we make the fish tank interesting and educational for kids?

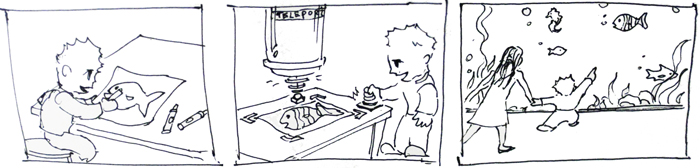

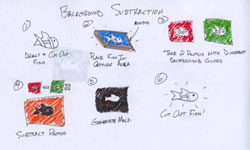

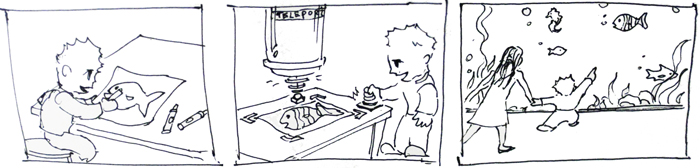

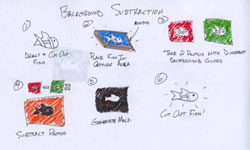

Fish Capture Extracting the “fish” portion of an image is a challenging computer problem. We needed a way to take what the camera sees and decide which areas are fish, and which are not. To do so, we tried numerous methods, from bluescreening, to outline detection, to making the kids trace their own fish on the computer. The method that worked best was an augmented form of background subtraction. Using this method, the user performs the following simple steps:

- Cut out drawn fish

- Place fish on teleport table

- Wait for fish to show up on preview screen

- Press "Create" button to send fish to the tank

The goal of the interface was to be as simple as possible. Minimize the number of steps and actions required of the user. Adding a second button was a compromise we had to make to allow users to adjust the direction of their fish. We wanted users to only have to visit the camera station once.

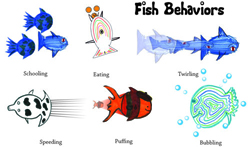

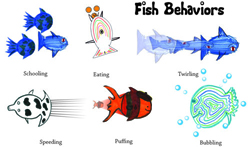

Making the fish Interesting and Educational. Early prototypes focused on fish behaviors derived from the real world: eating, chasing, fleeing, and schooling. However, because it was almost impossible to visually distinguish these behaviors from regular swimming, children were either oblivious or quickly lost interest. To counteract this, we added unusual, highly visual behaviors. We changed our emphasis from learning about ecosystem interactions through observation to generating intrigue about why fish behave the way they do. The goal was to get children to become interested in what attributes cause what behaviors, and come up with hypotheses they can test through repeated experimentation.

Testing

We worked with children from the Nueva School of Hillsborough to better understand how real world users would interact with our system. Over the course of a month, we conducted four test sessions. Each session, we worked with three to six children in third to fifth grade over the course of an hour as they took our system for a test drive. These kids taught us a few very valuable lessons about our project.

- Normal is boring. The children we worked with loved coming up with wild and crazy creations. From penguins to dogs to Abraham Lincoln on a surfboard, we wound up with a lot more than fish in our tank. This made a difference on our side too. We found we had very little time to capture children’s attention on the screen before they found it boring, and so we had to add some wild and crazy behaviors that would never occur in nature.

- Kids love rich visuals. Early on, we incorporated several less visible behaviors such as schooling and finding food, but kids didn’t notice their fish doing anything other than swimming. They really only paid attention to the behavior of their fish after we added highly visible behaviors like sparking, puffing, and twirling. We found that rich visuals wound up being a key to keeping children’s attention on the screen.

- New tools should be as simple, flexible, and effective as possible. In our first prototype we learned that kids were too imaginative to be accommodated by cookie-cutter fish outlines. Over the next several prototypes we discovered that while we needed flexibility to our capture system, children were uncomfortable with any tool that required more than a simple button push or two. We also found that kids needed a preview of exactly what they were going to add to the system, because they were incredibly dissatisfied with visual noise that wound up captured along with their fish.

- Pushing a giant red button is fun, and it should do something fun. We built giant red buttons for kids to interact with the SeaMe world. In one prototype, the first push of a button captured a fish image and a second press put the fish in the tank. Kids did not understand that they needed to press the button again, because they expected that a single press of the button would do what they wanted: put the fish in the tank. We settled on having multiple buttons, each for a distinct action like flipping the fish horizontally or putting the fish in the tank.

The Kids

We owe a special thanks to the children we worked with at the Nueva School of Hillsborough. They told us what we were doing wrong, what we were doing right, and what we were doing awesome. Thanks, too, goes out to Tracy Plowman for making our sessions with these kids possible.

|

|

|

The Vision

The Vision

Learning Goals

Learning Goals

Prototyping

Prototyping

Testing

Testing

The Kids

The Kids